Women In Indonesian Politics

- The Complex Political Landscape of Developing Nations

- Women Political Leaders

- Indonesia’s History of Women’s Participation

- Advancements for Indonesian Women

- Cultural Barriers

- Internal Party Dynamics

- Family Obligations

- Awareness and Education

- Case study: Women Representation in Local Parliament

- Conclusion: Steps Needed to Increase Women’s Political Participation

The Complex Political Landscape of Developing Nations

In many developing countries, the complex intersection of political and economic tensions poses a significant challenge. Governments often escape accountability, corruption thrives, and certain segments of society remain inadequately represented. These issues stem from the unique pressures and dynamics that shape the political landscape of developing nations.

Urbanization and rising education levels contribute to heightened political awareness, particularly among previously non-politicized populations. As more citizens demand political and economic participation, the system struggles to accommodate them. This places strain on political institutions and can lead to unrest if left unaddressed.

Developing nations must find ways to build more inclusive, transparent, and accountable political systems. Doing so will empower citizens, reduce corruption, and ultimately create a more just society. It is a difficult task, but a worthy challenge that developing nations must undertake.

Huntington’s Prediction of Heightened Political Awareness Proves Accurate

In many developing countries, urbanization and rising education levels are contributing to heightened political awareness, particularly among previously non-politicized populations.

As these countries undergo economic development and modernization, there are increasing migration flows from rural to urban areas. This rapid urbanization brings large populations together in cities, fostering information exchange and raising awareness of political issues. With greater access to media, technology, and diverse viewpoints in urban environments, people become more politically engaged.

Similarly, as education levels increase in developing nations, citizens become more informed and develop greater interest in the political process. Public schooling exposes individuals to civic concepts, enabling them to better understand their rights and responsibilities. Higher education provides analytical skills to critically assess political leaders and policies.

Overall, Huntington’s prediction that urbanization and education would lead to heightened political awareness in the developing world has proven accurate. These socioeconomic changes have galvanized previously marginalized groups and intensified demands on political systems. Managing the rising political engagement of newly aware citizens poses an ongoing challenge for governments in developing countries.

Women Political Leaders

The 20th century saw the rise of many exceptional women to the highest political leadership roles across the globe. Most notable among them were figures like Indira Gandhi, who served as Prime Minister of India for nearly two decades and remains the country’s only female premier thus far.

As daughter of India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Gandhi grew up immersed in politics. After years of supporting her father and serving in various roles within the Indian National Congress party, she went on to become Prime Minister in 1966. Gandhi would serve multiple terms leading India, making bold moves like authorizing a nuclear test in 1974 and initiating a state of emergency from 1975 to 1977. She became known internationally as a champion for developing nations. Tragically, Gandhi was assassinated by her own bodyguards in 1984 while still in office.

Other groundbreaking women leaders of the era were Isabel Perón of Argentina, who was the world’s first female president, as well as Corazon Aquino of the Philippines, who restored democracy after the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos. Overall, the 20th century marked a major shift in women rising to power on the global political stage and reaching new heights of leadership.

Indonesia’s History of Women’s Participation

Indonesia has a rich history of women’s participation in politics. In 1928, the inaugural Women Congress was held, marking an important milestone for women’s political involvement. Over time, women gained increasing representation through the 1955 elections during parliamentary democracy, the New Order era under Suharto’s presidency, and in the post-New Order period after Suharto’s resignation in 1998.

Significant progress came in 2004 with the implementation of a 30% quota system for women’s representation in the national parliament. This affirmative action policy helped increase the number of women parliamentarians at the national level, though it has been less effective at boosting women’s participation at the local level. Overall, Indonesian women have made important strides in political participation throughout the nation’s history, from the early Women Congress to the contemporary quota system. Challenges remain, but the long-term trend points to expanding roles for women in Indonesia’s political landscape.

Advancements for Indonesian Women

Indonesia has seen several advancements for women’s political participation in recent decades. One of the most notable was the implementation of a 30% quota system for women in 2004. This quota mandated that 30% of a political party’s candidates and parliamentary seats must be filled by women.

The quota system has significantly increased the number of women in parliament. In the 2004 election, women won 11.3% of parliamentary seats, up from 8% in the previous election. By 2009, this percentage had jumped to 18%, largely attributed to the quota. While Indonesia has yet to reach the 30% target, the quota represents an important affirmative action policy to improve women’s political representation.

Additional progress includes granting voting rights to women in 1946 and allowing women to stand for election in 1952. With the quota system and growing societal openness to women leaders, female participation in Indonesian politics continues to expand. However, persistent challenges like cultural norms, internal party dynamics, and familial expectations demonstrate the need for further advancement.

Cultural Barriers

In Indonesia, cultural norms often act as impediments to women’s political participation and leadership. Traditional gender roles portray women as subordinate and limit their acceptance in positions of power. Many elements of culture reinforce the notion that women belong in the domestic sphere caring for family rather than the public sphere of governance and leadership. These norms can be pervasive, shaping social expectations and making it difficult for women to be seen as legitimate political candidates and leaders.

Indonesian culture has strong patriarchal roots, contributing to attitudes that politics is primarily a man’s domain. The perceived traits of a good leader are also heavily skewed toward masculine qualities like assertiveness, competitiveness and dominance. Women in leadership threaten traditional concepts of power and authority. They may face questions over their toughness, capability to handle crises, and ability to command respect from subordinates. Overcoming such cultural barriers requires shifting mindsets on appropriate social roles for women as well as the attributes of leadership.

Internal Party Dynamics

Within political parties themselves, existing power structures and internal systems often perpetuate gender biases that hinder the progress of women in politics. Leadership positions are disproportionately held by men, who may actively or passively resist initiatives to increase women’s leadership roles. Patriarchal norms become deeply embedded within party culture and operations.

Many political parties lack strong policies and mechanisms to recruit, support, and promote female candidates. Women seeking leadership positions or nominations to run for office frequently encounter obstacles related to lower perceived competence, exclusion from influential networks and activities, and lack of structural accommodations for women’s needs. Overcoming ingrained organizational inertia and entrenched mindsets presents an ongoing struggle.

Transforming internal party dynamics requires multifaceted approaches. Policies mandating minimum proportions of female party officials and political candidates can provide impetus for change. Robust mentoring, training, and advancement programs focused on women establish structural pipelines and address skill gaps. visibly modeling diversity in leadership posts signals an inclusive culture. Flexible meeting times and childcare help enable women’s participation. Continual advocacy and pressure from reform-minded members keeps gender equity on the agenda. Fundamentally, parties must critically examine biases in order to cultivate more egalitarian ethos and practices over the long term.

Family Obligations

In Indonesia, family obligations present a significant barrier for women seeking political leadership positions. Traditional gender norms often dictate that a woman’s primary role is in the domestic sphere, caring for children and managing the household. Many women face resistance from husbands, parents, and extended family when considering political careers, as politics is still widely seen as part of the male domain.

The expectations to be primary caregivers and run households put extensive demands on women’s time and energy. Politics requires long work hours and extensive travel, which is difficult to balance with family duties. Women considering politics may face discouragement from family members who worry it will detract from their ability to properly care for children and fulfill other familial responsibilities.

Cultural attitudes that politics is not an appropriate path for women also lead many families to actively dissuade women from pursuing leadership positions. In a society where women are expected to put family first, their ambitions beyond the home may be criticized. Many women opt not to pursue political careers to avoid family conflict and maintain harmony.

Overcoming entrenched gender roles and shifting cultural mentalities is key to enabling more women to take on political leadership in Indonesia. Unless families become more supportive of women’s political aspirations, family obligations will continue deterring capable female leaders. Greater education and advocacy efforts to promote more progressive gender attitudes could foster an environment where women feel empowered to take on public leadership roles.

Awareness and Education

Limited political awareness and educational disparities present additional obstacles for women pursuing leadership roles in Indonesia. Many women, especially those in rural areas, lack access to civic education programs teaching the fundamentals of political engagement. Without a foundational understanding of political systems and processes, participating meaningfully becomes difficult. Educational limitations also factor into the equation, as Indonesian women have lower literacy rates and fewer opportunities for advanced studies compared to men.

Pursuing political office requires a certain degree of education and political know-how. To increase women’s representation, grassroots educational initiatives focused on political literacy are essential. Existing programs led by civil society groups demonstrate the power of targeted education in empowering women and girls to become more politically active. Expanding these efforts, alongside boosting educational attainment overall, will open more doors for women to take on leadership positions. Greater awareness and education serve as key steps toward achieving gender parity in Indonesia’s political realm.

The Beginning of Women Representative in Indonesian Political System

Ten years after Indonesia independence, there was a first general election that was held in 1955 and will be always held every five years after that. The numbers of political parties which enter the election always different and that makes different calculation of women participation (Parawansa, 2005). The election of 1955 has been called to be the first opening for Indonesian women to be representative in parliament, there are seven candidates came from women’s organization and a few from political parties which made 17 women are elected to the legislation (Parawansa, 2005).

In New Order era when Soeharto become the president, Indonesia use a single party which is a major party is a dominant one, and women representation are determined by the party-elites because they can’t do anything if they don’ have anyone who strong enough to bring them to the top, so the candidates must be have close relationship with the elites, also in this era, women don’t involved directly in election campaign and they there is a gap between the candidates and the voters. (Parawansa, 2005).

End of the New Order regime is the start of reformation in Indonesia, the first election in 1999 has result that 45 women are elected with total number 500 of DPR members also there are not so much difference from provincial election which is in East Java parliament just have 11 women in parliament out of 100 members. (Siregar, 2005). It’s conclude, in Indonesia, women participation in politic still low after post-new order. Women participation in several Indonesia province are less than 30 percent and some of the provinces are less than 10 percent legislators are women (Rhoads, 2012).

With the new regulation on women participation in politics that is a 30 percent quota for women legislative candidate and a 30 percent quota for women in party leadership had been made in 2003 (Rhoads, 2012), even there is a chance for women enter political arena in Indonesia, the rate of women representation in legislature still remained low.

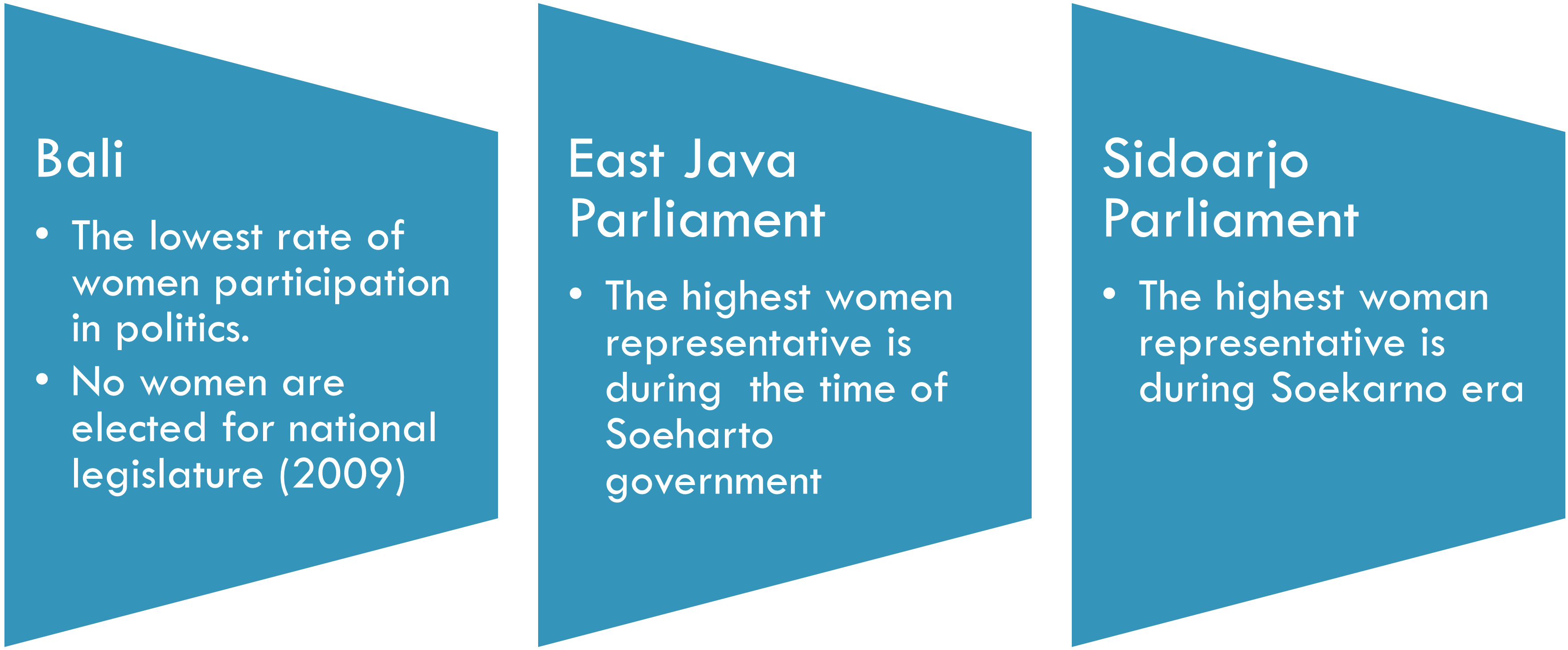

Case study: Women Representation in Local Parliament

Bali, was the lowest rate of women participation in politics. Even there is Balinese women run for the candidate in 2009, there is no women are elected for national legislature. In Indonesia context, women are the least represented at the local parliament, in total there are just 12 percent of all regional legislator from 491 district in Indonesia and in Bali, there are just make 7 percent of district level legislator. Many factors lead the reason why there are a few women in Indonesia political system that will be more describe in the next topic.

Slightly different from national parliament, the representative from East Java parliament was little bit higher from national parliament in the period 1982-1987 while the lowest was 10.5 percent. But, the similarity between East Java regional and national parliamentary was the highest women representative is during the time of Soeharto government.

In the Sidoarjo parliament, the highest percentage is 14.8 percent in 1956-1957, meanwhile the lowest was 4.4 percent is in the period 1999-2004. Different from the East Java regional and national parliamentary that the lowest percentage was during Sukarno Era (1945-1965), the Siduarjo parliament has the lowest percentage during reform era (1998 onwards). It means, the decentralization of district did not always improve the representation of women in Siduarjo.

From the Soekarno government in 1945, women representation in parliaments in Indonesia did not significantly improve, but there was a strong motivation for women activist to demand greater chance for woman in 2004 elections.

Women Struggle for Becoming Member of Parliament

Parliament is have a job to represent all the society, they are the representative of Indonesia citizens, but most of parliament members are men and just a few of woman. It become the challenge of Indonesian government to take this problem serious because Indonesia is using democratization system in the government it means all people can be parliament if they are compatible to doing that. In 2004 election, many women is taken in place which they can’t win, the example is they being placed far down the party list which is the chances for being elected is low.

Indonesian cultures also still deeply into patronage, money politics, also patriarchal. All parties expect to provide goods in return for votes in election. Money politics is often happening in political campaign for general election, such as patron-client relationship. The patron often is the candidate from the party and it use broker or tim sukses who offers goods or services to the client. The barrier of the women to enter political party is because of the high cost with limited public funding.

In Indonesia, awareness of gender and equality and justice issues is still low and most of people still patriarchal about women roles. Based on the survey in 2012 by CSIS, 86,3 percent of respondents agrees that women could work outside of home but have primary job that take care of household. That mean, Indonesia doesn’t trust women to take a lead, they still think that man should be the leader.

The Future of Women Representation in Politic

There are a few major associations of women’s organization which can help to increase representation of women in parliament such as Kongres Wanita Indonesia (KOWANI) and BMOIWI (Federation of Indonesian Muslim Women Organizations). If that organization can work together effectively, it can increase women representation. To increasing and promoting women participation in electoral process, the International Foundation for Electoral System with Center for Political Studies (PUSKAPOL) University of Indonesia worked with KPU and Elections Supervisory Agency (BAWASLU) to promote women’s representative to electoral management bodies.

The other ways to increasing the representation of women in political parties is by introducing the quota system within political parties and ensuring that women have chance in political parties or become candidate for general election. But, there is no use if woman had no skill to become candidate, so its needed to empowering women with education, training and increased access to information.

Effort to women representation must accompanied with the improvement of the democracy quality because parliament must represent all members of society.

Conclusion: Steps Needed to Increase Women’s Political Participation

While Indonesian women have made important strides, more work remains to foster women’s full participation and leadership in the political sphere. Key steps needed include:

- Changing cultural mindsets and attitudes to promote the acceptance of women leaders

- Reforming internal party processes to be more equitable and inclusive

- Providing support systems that enable women to balance family obligations

- Launching civic engagement programs to increase women’s political awareness

- Expanding educational opportunities for girls and women

- Allocating funding and resources to empower women candidates

The path forward requires a comprehensive, coordinated effort across all levels of society. From grassroots advocacy to policy reforms, impactful change hinges on a collective commitment to gender equity as a core value. With ongoing persistence and unity, Indonesian women can achieve equal representation and voice in the political realm.