Indonesia Political Institutions, Political Party, And Interest Group

- Introduction

- Colonial Era

- Post-Revolution

- Guided Democracy

- The New Order Regime

- Reformation Era

- Contemporary Politics

- Critical Political Issues

- Political Culture

- Political Dynasties

- Legislative Institutions

- Models of Legislative Structure

- Representation Models in Legislatures

- Executive Institutions

- Limits on Executive Power

- Judicial Institutions

- Bureaucratic Institutions

- Legislative History of Indonesia

- Volksraad (1918-1942)

- Badan Penyelidik Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan (BPUPK) (1945)

- Central Indonesian National Committee (KNIP) (1945-1949)

- United States of Indonesia (RIS) (1949-1950)

- Parliament of the Republic of Indonesia (1950-1959)

- Gotong Royong Parliament (1960-1965)

- Temporary People’s Consultative Assembly (MPRS) (1965-1968)

- People’s Representative Council (DPR) (1968-1999)

- Reformasi & Amendment of 1945 Constitution (1999-2004)

- Post-2004

- Executive Institutions in Indonesia

- Judicial Institutions in Indonesia

Introduction

Indonesia’s complex political history has witnessed several pivotal periods that have shaped the nation’s trajectory. From colonial rule to post-independence experiments with democracy, Indonesia’s political landscape has evolved through various ideological influences, power struggles, and governance models.

Tracing this rich historical tapestry offers insights into Indonesia’s contemporary political dynamics. The interplay between colonial legacies, nationalism, political ideologies, institutional development, and cultural influences has molded Indonesia’s political culture and structures.

Exploring the twists and turns of Indonesia’s political journey reveals how certain epochs left indelible marks. The shifts between centralized and decentralized power, democratic aspirations and authoritarian control, and consensus-based and individual-centric leadership models underscore the fluid nature of Indonesian politics.

While turbulent at times, Indonesia’s political maturation reflects the difficulties of nation-building. As the world’s largest archipelagic democracy continues to grow, the significance of past political watersheds becomes more evident. This examination of Indonesia’s complex political history provides an interpretive framework to analyze the currents shaping its future.

Colonial Era

The colonial era in Indonesia was marked by several key developments that impacted the nation’s political and economic trajectory. One major feature was the introduction of social stratification by the Dutch colonial rulers. This involved categorizing indigenous Indonesians into social groups based on criteria such as occupation, income, and proximity to the colonial administration.

At the top were the European settlers and colonial administrators. Below them was a small upper class of Indonesians who had roles in the civil service or private enterprises. The vast majority of Indonesians were in the lower social strata, providing manual labor in plantations, public works projects, and the informal economy. This stratification served to entrench colonial rule by elevating indigenous elites who supported Dutch interests.

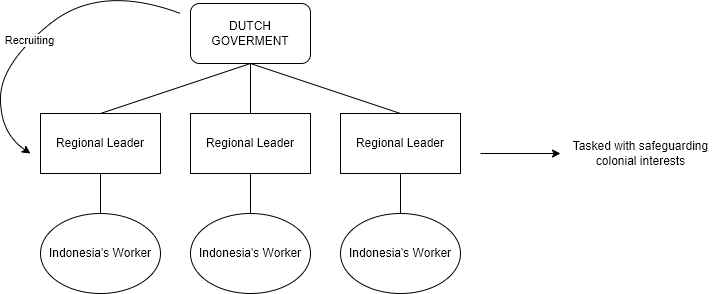

Another defining aspect of the colonial era was the Snouck Hurgronje system, named after Dutch advisor Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje. Also known as the Ethical Policy, it involved the colonial administration recruiting indigenous civil servants exclusively from aristocratic families. This aimed to co-opt the indigenous elite by offering them privileged positions and benefits. Over time, this resulted in native bureaucratic and military corps developing parallel to the European apparatus. The Snouck system had long-term impacts by shaping an influential class of educated Indonesians who would play key roles in the independence movement. However, it also reinforced social divisions between elites and the general population.

Post-Revolution

The post-revolution period in Indonesia experienced constitutional democracy, yet the parliamentary system proved challenging due to party fragmentation and frequent cabinet changes. After the revolution and independence from Dutch rule, Indonesia adopted a parliamentary system of government. Multiple political parties emerged, resulting in a fragmented party system with no single dominant party. This made it difficult to form stable coalition governments.

Cabinets during this time period were short-lived, with frequent collapses and reshuffling of ministers. On average, a new cabinet was formed every nine months between 1950 to 1957. The high rate of cabinet turnover was partly due to personality conflicts between ministers from different parties. It also reflected unsettled conditions as the new nation grappled with economic troubles and regional rebellions. The post-revolution years saw a vibrant democratic process, but political instability hampered effective governance.

Guided Democracy

The Guided Democracy era under President Sukarno saw notable deviations from constitutional norms, marked by strong presidential dominance and limited roles for political parties.

During this period from 1959 to 1965, Sukarno exercised near-absolute control over the political system. The 1945 constitution was replaced with a new provisional constitution in 1959 that centralized executive power in the presidency and weakened parliamentary oversight.

Sukarno also dissolved the elected parliament and replaced it with an appointed parliament. This allowed him to bypass parliamentary opposition and rule by decree. Political parties were forced to join together under one party, the Indonesian Nationalist Party (PNI), which further consolidated Sukarno’s control.

The Guided Democracy years represented a shift away from Western-style parliamentary democracy toward what Sukarno termed “Guided Democracy.” This was justified as a transitional phase suited to Indonesia’s national character and level of political development at the time.

In practice, Guided Democracy meant strict limits on political freedoms and party competition. The role of parties was reduced to mobilizing mass support for government policies rather than formulating alternative platforms or ideologies. Parliament became a rubber stamp for Sukarno’s policies.

Guided Democracy thus marked a period of unchallenged presidential dominance and the erosion of constitutional checks and balances. However, the system proved unstable and was unable to manage socioeconomic challenges, leading to Sukarno’s eventual downfall. Nevertheless, it left a legacy of executive assertiveness that continued to influence Indonesian politics.

The New Order Regime

The New Order regime, under President Soeharto, emphasized Pancasila and constitutional democracy but with a strong executive. The regime consolidated power over time.

Some key aspects of the New Order period:

- Pancasila was promoted as the sole ideological foundation of all political parties and organizations. This emphasized national unity and rejected communism.

- The regime claimed to uphold the 1945 constitution and honor constitutional democracy. In practice, democracy was tightly managed and controlled.

- President Soeharto as head of state dominated the political system. The role of the People’s Consultative Assembly declined.

- The military (ABRI) held appointed seats in parliament and served a sociopolitical role alongside defense matters.

- Golkar, the regime’s political vehicle, consistently won elections. Other parties were allowed but had limited room for maneuver.

- Over time, the regime consolidated power by limiting dissent, controlling the press, restricting civil society, and gaining business interests. It created a stable environment for economic development.

- Regional rebellions in the late 1950s consolidated central authority. An anti-communist purge followed the alleged 1965 coup attempt.

- The New Order brought over 30 years of authoritarian stability. But reforms were needed by the late 1990s due to social pressures, economic crisis, and political stagnation.

Reformation Era

The Reformation era followed the New Order regime, aiming to correct the excesses of the past and emphasize democratic principles and parliamentary oversight. This period ushered in significant political reforms and a transition to democracy.

Some key aspects of the Reformation era included:

- Constitutional reforms to limit presidential power and strengthen checks and balances. Amendments aimed to empower the House of Representatives (DPR).

- Decentralization reforms to give greater autonomy to local governments. This shifted power away from the central government.

- Electoral reforms such as direct presidential elections, allowing citizens to directly elect the president and vice president.

- The emergence of new political parties and a multi-party system. Restrictions on political parties were lifted.

- Greater press freedoms and reduced censorship. This allowed for more transparency and public discussion.

- A push to address human rights violations under the New Order regime. People demanded accountability for past abuses.

- East Timor’s vote for independence in 1999, ending Indonesia’s annexation. This shifted Indonesia’s political boundaries.

- A growth in political participation and activism. More citizens became involved in the political process.

Parliament took on a more assertive role during this era, exercising oversight and constraints on the presidency. Overall, Indonesia transitioned from an authoritarian regime to a democracy, albeit still imperfect and evolving. The Reformation era set the stage for Indonesia’s contemporary political dynamics.

Contemporary Politics

Transitioning into Indonesia’s contemporary political landscape, the democracy movement remains a dynamic force, rooted more in societal dynamics rather than individual leadership. The mass movements that emerged in the late 1990s, calling for democratic reforms and the end of authoritarian rule, reflected a societal awakening and desire for change. This organic, grassroots energy served as the catalyst for Indonesia’s transition to democracy.

While past authoritarian leaders like Suharto often held tight control, today’s democracy relies more on diffuse support within society. The contemporary democracy movement emerges through collaboration and coordination among various groups - students, labor unions, women’s organizations, journalists, activists and more. Rather than a top-down structure, it operates through horizontal linkages within civil society.

The multifaceted nature of governmental functions is also evident in the diverse roles played by various institutions in Indonesia’s contemporary politics. The executive, legislative, and judicial branches, along with the bureaucracy, each contribute unique elements to governance and oversight. The executive, consisting of the president, vice president and cabinet, oversees governmental administration and policymaking. The People’s Representative Council (DPR), representing legislative functions, enacts laws and budgets. The Supreme Court and Constitutional Court fulfill judicial duties of upholding justice and interpreting the constitution. Meanwhile, the far-reaching bureaucracy implements policies and delivers public services across the nation.

This interplay of institutions illustrates the complexity of orchestrating governmental responsibilities within a democratic system. It also highlights the diffusion and separation of powers, unlike the centralization of authority under past authoritarian regimes. Understanding these institutional dynamics provides deeper insight into Indonesia’s evolving democratic landscape.

Critical Political Issues

Indonesia faces several critical political issues that shape its contemporary landscape. Three major areas stand out: elections, the interplay of religion and politics, and challenges associated with decentralization.

Elections

Elections in the post-Suharto era have been meaningful in transitioning Indonesia to democracy. However, money politics has become entrenched, undermining the democratic process. Vote buying distorts policymaking as elected officials cater to wealthy backers over constituents. Strict enforcement of campaign finance laws is essential. Low voter turnout also threatens meaningful participation. Engaging voters through education and limiting practical barriers to voting like transportation access could boost turnout.

Religion and Politics

The interaction between religion and politics holds profound influence in Indonesia. Islamist parties have gained traction, raising questions about Indonesia’s secular foundations. Hardline religious groups pressuring for Islamic law also threaten pluralism. However, most Indonesians reject formal Sharia implementation, preferring secular democracy. The challenge is balancing Indonesia’s Muslim identity while protecting minorities and upholding democratic principles.

Decentralization

Decentralizing power from Jakarta to local administrations aimed to improve governance and services. However, limited human resources and corruption at local levels have hindered progress. Central support through training and auditing local institutions could enhance outcomes. Effective decentralization requires capable local leaders focused on constituents, not personal gain. With strengthened local capacity, decentralization can help tailor policies to community needs across Indonesia’s diversity.

Political Culture

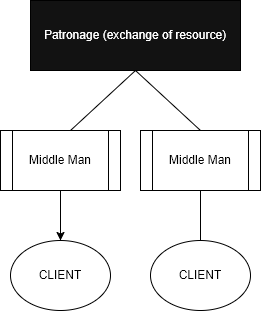

Indonesia’s political culture, shaped by the process of political socialization, exhibits diverse orientations. During the New Order era under President Suharto, hierarchical power structures and patronage systems characterized political culture.

Suharto’s neo-patrimonialistic system focused power in the presidency rather than democratic institutions. This contributed to a subject political culture in which citizens largely complied with government dictates rather than actively participating. The government emphasized national ideology and unity over pluralism.

Citizens were politically socialized to accept the dominant role of Golkar, the government party, as well as the military’s dual function of security and sociopolitical affairs. Traditional patron-client ties between elites and followers were incorporated into the political system.

Overall, political culture under the New Order regime tended to emphasize order over freedom, consensus over dissent, and hierarchy over grassroots participation. The transition to democracy initiated efforts to change this culture by promoting active citizenship, power-sharing, and institutional accountability. However, legacy effects of previous authoritarian rule continue to shape political attitudes and behaviors.

Political Dynasties

The intriguing phenomenon of political dynasties is present in Indonesia’s political landscape, with the most notable being the Sukarno family. Their enduring influence stems from strong institutional foundations and effective political strategies that have enabled the dynasty to thrive across generations.

The Sukarno family’s dynasty began with Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, who laid critical groundwork during his presidency from 1945-1967. He allowed independent structures to develop that provided the foundations to sustain the dynasty beyond his leadership. This included the establishment of the Partai Nasional Indonesia (PNI) in 1927, which became a powerful political institution even after Sukarno’s death.

The PNI gave the Sukarno family an established base of support that persisted as a dynasty-sustaining mechanism. Later presidents and leaders found it difficult to dismantle the PNI, demonstrating the dynasty’s strength. Through this enduring party structure and identity, the Sukarno name maintained its potency in Indonesian politics.

While some observers have cited the absence of charismatic successors as a vulnerability for the Sukarno dynasty, the institutional structures built early on have compensated for this weakness. The family has relied on organizational mechanisms rather than sheer personality to perpetuate its influence across generations, making it a formidable dynasty within Indonesia’s political arena.

Legislative Institutions

Legislatures are representative bodies with vital governance functions. They are distinguished by key features including a multi-member composition and formal equality among members.

The primary function of legislatures is to legislate. This involves deliberating, debating, and voting on bills to enact laws. Legislatures serve as lawmaking bodies that create statutes to regulate society.

In addition to lawmaking, legislatures have several other crucial duties:

-

Appointing government officers - Many high-ranking officials in the executive branch are nominated by the legislature. This includes cabinet members, judges, ambassadors, and leaders of agencies.

-

Judicial activities - Legislative bodies often engage in judicial functions like impeachment trials and investigations into government misconduct.

-

Investigations - Legislatures have oversight power to investigate operations and activities of the government through hearings, audits, and inquiries.

-

Ombudsmen role - Legislators frequently act as representatives for citizens’ interests and grievances related to the government. They serve an ombudsman role responding to public complaints.

By carrying out these diverse functions, legislative institutions form an indispensable pillar of governance and democracy. The legislative branch acts as a check on executive power and upholds the will of the people through elected representatives.

Models of Legislative Structure

Transitioning to legislative structures, two prevalent models exist: the parliamentary system with a separate head of state and symbolic powers, and the presidential system where the chief executive holds dual roles as head of state and government.

In a parliamentary system, the head of state (monarch or president) possesses ceremonial powers but the head of government (prime minister) and cabinet conduct day-to-day governance and are drawn from the legislature. The executive is thus dependent upon legislative confidence.

In contrast, presidential systems fuse the roles of head of state and government in a president who serves as chief executive. The president appoints the cabinet but they are not members of the legislature. As the executive and legislative branches are independent, the president can’t dissolve the legislature but faces the possibility of impeachment.

Parliamentary systems promote greater cooperation between the executive and legislative branches. The fusion of powers enables quicker decision-making during crises. However, the reliance on legislative confidence can create instability and weak, short-lived governments.

Presidential systems provide more separation of powers and checks and balances. But conflicts can arise between the executive and legislature over appointments, budgets, and policies. Deadlock becomes a possibility.

Overall, both systems have trade-offs in governance efficiency, representation, accountability, and power balances. The selection depends on a nation’s context, culture, and specific needs.

Representation Models in Legislatures

According to Marcus, there are three main representation models for legislators: delegate, trustee, and politico.

The delegate model of representation refers to when a legislator acts on the expressed wishes of constituents, regardless of the legislator’s own opinion. In this model, the legislator serves as a conduit for the preferences of their district or state. They aim to reflect the views of their constituents rather than their own judgment.

In contrast, the trustee model of representation is when legislators use their own judgment when voting, acting in what they believe are their constituents’ best interests, even if these actions contradict public opinion. Trustees are not bound by pledges to voters and feel no obligation to follow constituents’ instructions. This model assumes that constituents have selected their representative for their wisdom and integrity.

Finally, the politico model combines elements of both the delegate and trustee models. Politicos typically promise to support the broad policy views of constituents but maintain independence to apply their discretion and expertise on individual issues. This flexible approach recognizes that legislators cannot be held to rigid standards on every issue and vote. The politico legislator balances responding to public opinion with acting on their own judgment.

Executive Institutions

Executive institutions serve critical functions in governance. These include diplomacy, where the executive engages in relations with foreign governments and international bodies. Emergency leadership is another key function, with the executive mobilizing resources and personnel during crises.

Budget formulation is a central responsibility, as the executive drafts financial plans and submits them for legislative approval. Control of the military also falls under executive purview, encompassing deployment of armed forces and oversight of national security.

Administration is a major duty, with the executive establishing departments, agencies, and programs to implement policies. Policy initiation allows the executive to put forth legislative proposals and shape the political agenda.

Finally, executives fulfill symbolic leadership as head of state, acting as the ceremonial figurehead and representing the nation domestically and globally. Through these diverse functions, executive institutions wield substantial authority and influence in governance.

Limits on Executive Power

While executive institutions often wield significant power, their authority is not absolute. Various mechanisms serve to impose checks and balances on the executive branch.

Term Limits

One of the most direct ways to limit executive power is through term limits, which restrict the number of terms or years an individual can serve as head of government. This prevents an unchecked consolidation of power and forces routine turnover in leadership. Many presidential systems constitutionally limit presidents to two consecutive terms in office.

External Sources of Power

Executive power can also face limitations imposed by external actors and sources of authority. These may include the military in some regimes, powerful economic actors, influential social/religious institutions, or even public opinion and media scrutiny. Though not formal limitations, these factors shape and constrict executive decision-making.

Institutional Constraints

Finally, constraints by other government institutions represent a significant check on executive authority. The legislative and judicial branches can block or overturn executive actions through legislation and review. An independent legislature can force negotiation and accountability. Empowered courts can deem executive policies unconstitutional. And quasi-independent agencies created by law can also curb executive power in their realms. The separation of powers baked into many government structures purposefully establishes these institutional constraints.

Judicial Institutions

Judicial institutions, commonly referred to as courts or judicial systems, serve crucial governance functions including conflict resolution, social control, protection of minority rights, and policymaking.

Courts aim to resolve disputes through application of relevant principles. Key justice principles that guide judicial systems include:

- Procedural fairness - fair and transparent procedures

- Substantive fairness - fair and reasonable outcomes

- Accessibility - ease of access to justice

- Efficiency - timely and effective dispute resolution

- Independence and impartiality - unbiased decision making

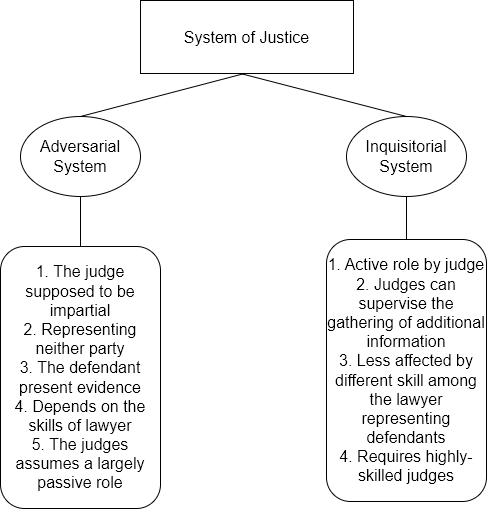

Two predominant legal systems are the adversarial system, where opposing parties present their cases and judges act as referees, and the inquisitorial system where judges take an investigative role.

Various types of law guide judicial institutions. These include:

- Natural law - universal principles derived from nature or divinity

- Positive law - established rules enacted by government

- Statutory law - written laws passed by legislative bodies

- Common law - law established by judicial precedent

- Civil law - governs relations between individuals

- Criminal law - classifies crimes and specifies punishments

Judicial institutions apply these laws and principles to fulfill their societal roles. The form and function of courts varies across political systems and jurisdictions.

Bureaucratic Institutions

Bureaucratic institutions form a crucial part of any governance structure, staffed by qualified officials who are responsible for policy implementation. Their primary purpose is to carry out the work of government that requires specialized expertise, within a hierarchical organizational structure designed to promote efficiency and accountability.

The bureaucracy is meant to operate based on a meritocratic system, recruiting and promoting officials based on their qualifications rather than political connections. Officials are expected to faithfully execute policies regardless of changing political leadership. They typically enjoy security of tenure to protect them from politicization.

Some key features of effective bureaucratic institutions include:

- Specialization and division of labor - Officials focus on distinct areas like finance, health, defense based on educational background and experience.

- Hierarchy and clear reporting structures - Lower level officials report to higher officials with decision making authority.

- Written rules, procedures and records - Standardized processes guide actions and preserve institutional memory.

- Merit-based recruitment and promotion - Appointments and advancement are based on skills and performance, not patronage.

- Tenure protections - Officials have job protections against politically motivated firing.

- Neutral competence - Actions are objective and non-partisan in nature.

By leveraging trained experts operating under well-defined rules and procedures, bureaucratic institutions aim to implement policies and deliver public services effectively and consistently. A capable, professionalized bureaucracy can provide stability and continuity for governance. However, bureaucracies can also become overly rigid and unresponsive. Finding the right balance is an ongoing challenge.

Legislative History of Indonesia

Indonesia’s legislative history can be divided into 15 periods from 1918 to 2004:

Volksraad (1918-1942)

This was the first legislative body in Indonesia established by the Dutch colonial government. It served in an advisory capacity to the Governor-General.

Badan Penyelidik Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan (BPUPK) (1945)

BPUPK was formed to prepare for Indonesian independence. It produced the draft constitution that became the basis for Indonesia’s 1945 constitution.

Central Indonesian National Committee (KNIP) (1945-1949)

KNIP functioned as a temporary legislative body after independence was declared in 1945. It appointed Sukarno as president and Hatta as vice president.

United States of Indonesia (RIS) (1949-1950)

The RIS legislature known as the Constitutional Assembly of the United States of Indonesia served during the short-lived federal state period.

Parliament of the Republic of Indonesia (1950-1959)

After the RIS dissolved, the unitary Republic of Indonesia was formed with its own parliament. This is sometimes referred to as the era of liberal democracy in Indonesia.

Gotong Royong Parliament (1960-1965)

After Sukarno dissolved the 1950 parliament and declared guided democracy, the Gotong Royong Parliament was formed and dominated by appointees.

Temporary People’s Consultative Assembly (MPRS) (1965-1968)

After Sukarno’s fall, General Suharto led a new order government. The MPRS served as the legislature during the transition.

People’s Representative Council (DPR) (1968-1999)

The New Order government under Suharto established the DPR as the lower house within a limited legislative system.

Reformasi & Amendment of 1945 Constitution (1999-2004)

After Suharto’s resignation, amendments were made to the 1945 constitution, including provisions related to the DPR.

Post-2004

From 1999 onwards, the DPR has been directly elected by the people every 5 years, starting in 2004. This represents Indonesia’s Reformasi era legislative body.

Executive Institutions in Indonesia

Moving to the executive structure in Indonesia, the 1945 Constitution established a presidential system with a president serving as both head of state and head of government. This structure was in place from 1945 to 1959.

The president was directly elected and could serve a maximum of two five-year terms. They had the power to appoint and dismiss cabinet ministers. The president was also the supreme commander of the armed forces.

In 1959, Indonesia moved briefly to a parliamentary system, but presidentialism was restored in 1965. From 1967 to 1998 during the “New Order” period under President Suharto’s authoritarian rule, the president held strong executive powers.

After the fall of Suharto in 1998, Indonesia’s post-reformation era saw the presidency retain its dominant position but with some limitations to presidential powers. Direct presidential elections were reintroduced in 2004.

The president and vice president are directly elected as a ticket and can serve a maximum of two consecutive five-year terms. The president heads the cabinet and has broad appointment powers over top military and government positions. However, the president’s ability to dismiss the legislature is limited, and presidential emergency powers are subject to parliamentary oversight.

Overall, Indonesia’s presidential system concentrates executive authority in the presidency, while incorporating some checks and balances. From the initial structure in 1945 to the present, the core role of the president as dual head of state and government has persisted.

Judicial Institutions in Indonesia

Post-Reformation Entities and Roles

The judicial system in Indonesia underwent significant reforms following the end of the New Order regime in 1998. Some of the key judicial institutions established in the post-reformation era include:

- Mahkamah Konstitusi (Constitutional Court) - Formed in 2003, the Constitutional Court rules on disputes over the constitutionality of laws and hear disputes on election results and the dissolution of political parties. It has the authority to review and strike down laws that are deemed unconstitutional.

- Mahkamah Agung (Supreme Court) - As the highest court in the judicial system, the Supreme Court hears appeals from lower courts. It also has the authority to review regional regulations and has jurisdiction over military courts.

- Komisi Yudisial (Judicial Commission) - Established in 2004, the Judicial Commission nominates candidates for appointment as Supreme Court justices. It also has the authority to maintain ethics and discipline in the courts.

- Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi (Corruption Eradication Commission) - Formed in 2003, the KPK investigates and prosecutes major cases of corruption. It has broader authority than the Attorney General’s office to wiretap and make arrests.

- Komisi Nasional Anti Kekerasan terhadap Perempuan (National Commission on Violence Against Women) - Established in 1998, this commission develops policies, monitors cases, and provides services related to violence against women.

- Komisi Ombudsman Nasional (National Ombudsman Commission) - Formed in 2000, the Ombudsman Commission oversees public services and investigates maladministration in the public sector. It has the authority to investigate complaints and issue recommendations.

These post-reformation judicial institutions have played important oversight, anti-corruption and public advocacy roles in the years since democratic reforms began in Indonesia.