Research Method in International Relations Study

International Relations (IR) is a relatively young field of academic study that emerged in the early 20th century. IR as a discipline is focused on the study of the international system, including relations between states, international institutions, non-state actors like NGOs and MNCs, global issues like climate change, and more.

IR draws upon various disciplines in the social sciences and humanities, including political science, economics, history, law, sociology, and philosophy. This multidisciplinary lineage means IR utilizes diverse theoretical frameworks and methodological approaches.

IR scholarship addresses both empirical questions and interpretative questions. Empirical research analyzes events, developments, or trends in world politics using scientific methods and evidence-based analysis. Interpretative research focuses more on understanding meanings, ideas, norms, identities and culture in the international system through critical analysis.

This multiplicity of research agendas has led to debates within IR on appropriate standards of rigor and disciplinary boundaries. Positivists argue IR should utilize the scientific method while post-positivists critique this approach.

Empirical–Interpretive Divide

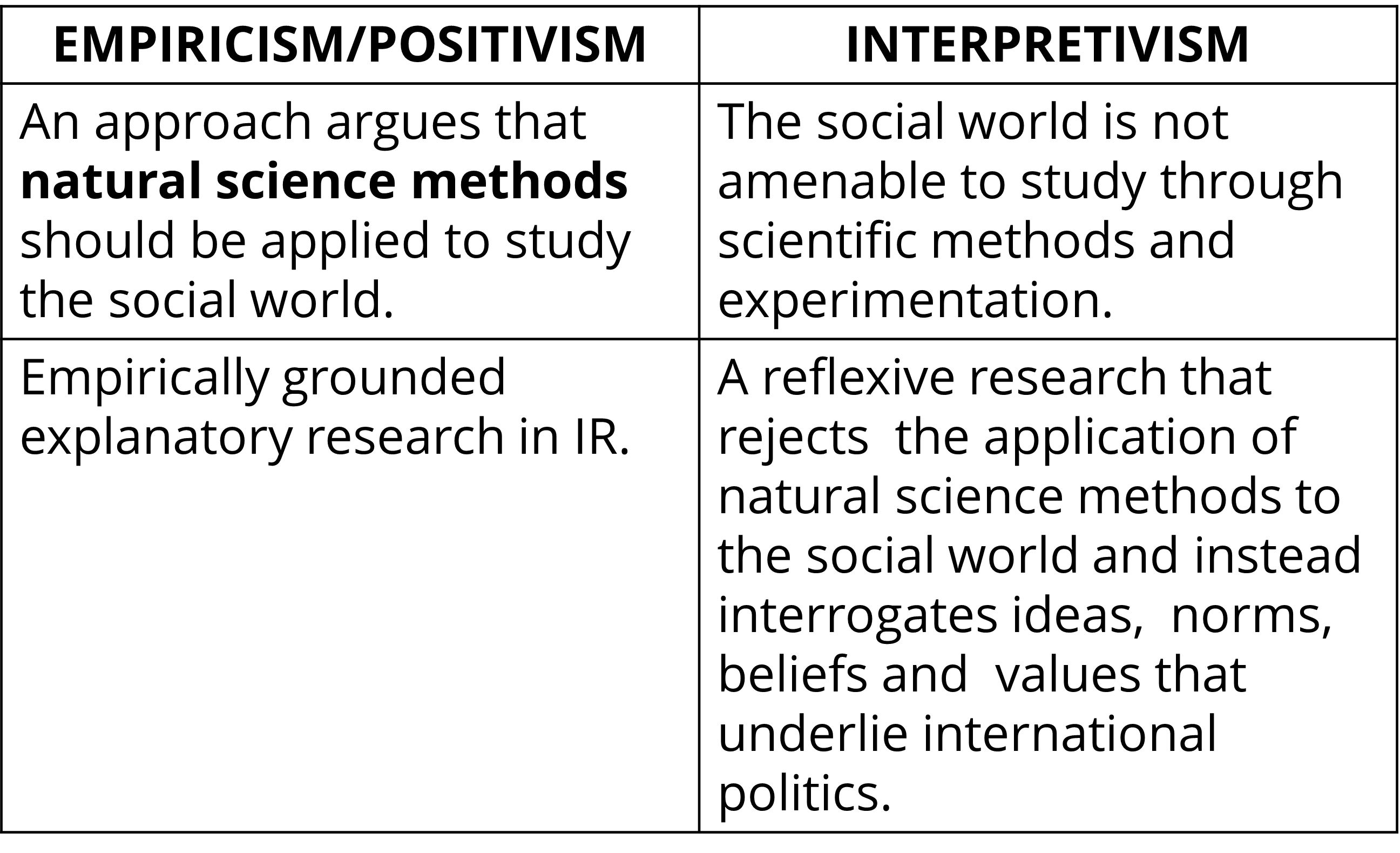

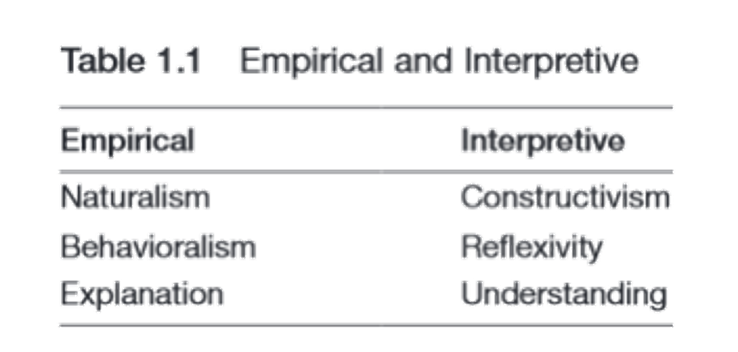

IR scholarship can be grouped into two broad epistemological traditions that advance competing claims as to what should be regarded as acceptable knowledge within the field: empiricism and interpretivism. This dichotomy replicates a divide that is evident across the social sciences and coalesces around the question of what knowledge is of disciplinary value and what knowledge should we strive to produce?

Empiricism generally holds that valid evidence of social phenomena should be derived through factual evidence produced via systematic and replicable research governed by established scientific methods. Empiricists promote the application of the scientific method to verify causal relationships and derive generalizable conclusions on the basis of empirical evidence.

In contrast, interpretivism eschews the notion that the study of society is analogous to the study of nature. Interpretivists argue that researchers cannot identify impenetrable regularities or discover constant conjunctions in human affairs akin to the physical sciences. The focus is more on understanding meanings, motives, reasons and other subjective experiences central to social life yet neglected by empirical techniques wedded to the data derived from observation of the external world.

Empiricism/Positivism

Empiricism in international relations aims to apply research practices from the natural sciences to the study of world politics. It is based on the broad assumption that knowledge can be accumulated through objective observation and systematic testing. Empiricists view international relations as a social science that should be studied in a measurable, replicable, and evidence-based manner. Theories can be generated through careful observation and then tested empirically. According to empiricists, international politics can be studied as an objective reality distinct from the perceptions of the researcher. The validity of theories is judged by their predictive power and ability to produce testable hypotheses.

Some key scholars associated with empiricism in international relations include Hans Morgenthau, who developed realist theory, and Kenneth Waltz, known for structural realism. Both approached the study of world politics with the intention of constructing testable theories that could explain and predict state behavior and international outcomes. Overall, empiricism remains a dominant epistemology within the field of international relations today.

Empiricism in international relations theory is based on the idea that the study of world politics should emulate the methods used in the natural sciences. There are three core principles that underpin empirical research in IR:

-

IR can be studied as an objective reality distinct from the researcher: Empiricists believe that international politics exists as an objective reality that is a world ‘out there’ beyond the researcher’s own subjective perceptions. Just as the natural world can be observed impartially, so too can the realm of international relations. The researcher is capable of studying IR in a detached, non-biased manner not influenced by their own values or identity.

-

Theories are held to the standard of predictive validity: A key test of an empirical IR theory is whether it can predict future events or behaviors. Empiricists develop explanatory and predictive theories that can anticipate how states or other actors will behave under certain conditions. The ability of a theory to accurately predict outcomes is a mark of its explanatory power and empirical validity.

-

Hypotheses must be falsifiable: In order for a theory to be considered scientific, it must be capable of being proved false. Empiricists propose hypotheses that make clear claims that can be tested systematically against evidence. If the evidence contradicts the hypothesis, then the theory has been falsified and must be rejected or revised. The requirement for falsifiability guards against theories that cannot be disproven.

Interpretivism/Reflectivism/Post-Positivism

Interpretivism draws upon a rich tradition in IR among scholars whose aim is not necessarily to explain events, developments or trends. Instead, it focuses on understanding the social meanings embedded within international politics. The aim is to unpack the core assumptions that underlie the positivist image of the world in an attempt to counter the perceived empiricist orthodoxy in IR.

Interpretivist research agendas seek to understand identities, ideas, norms, and culture in international politics. Some examples of interpretivist scholars are Richard Ashley and Robert Cox.

Interpretivism is based on some core principles:

-

The distinction between the researcher and the social world, implied by empiricists, should be rejected. The researcher intervenes in, or creates, observed social realities through their own role in knowledge production and thus alters the object under study.

-

The researcher and the research subject are mutually constituted through intersubjective understanding, and therefore the object of research does not have its own objective existence outside this mutually constituted relationship.

In summary, interpretivism in IR rejects the assumptions of empiricism and instead focuses on understanding meanings and identities in international politics through interpretive research agendas.

Empiricism Examples

Empiricism has been a dominant epistemological orientation within the field of International Relations, with many seminal works exemplifying this approach. Key examples include:

- Hans Morgenthau - A pioneering realist thinker, Morgenthau advanced a theory of international politics centered on the concept of power. In his classic 1948 work, Politics Among Nations, Morgenthau sought to develop testable propositions about state behavior derived from observations about the inherent nature of international politics. His theory of political realism was positivist in orientation, with the aim of creating generalizable knowledge about international relations through empirical study.

- Kenneth Waltz - Waltz’s 1979 book Theory of International Politics is considered a seminal text of neorealism. He adopted a structural approach, using empiricist methods of abstraction and logical deduction to create a parsimonious theory that stripped away variables at the domestic and individual level. Waltz tested propositions about the behavior of states operating under international anarchy through observations of great power politics. His theory aspired to offer predictive and falsifiable hypotheses.

- Neo-liberals - Scholars such as Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye articulated neoliberal institutionalist theories that recognized the importance of international institutions alongside state power. Their 1989 work Power and Interdependence used quantitative analyses of transnational flows and connections to substantiate their theoretical claims empirically. Neo-liberals adopted scientific methods aimed at developing probabilistic causal claims that could be tested against empirical evidence.

Interpretivism Examples

Interpretivists in IR draw upon a diverse range of theoretical perspectives and approaches that emphasize the constructed nature of social reality. While united in their skepticism of positivism, interpretivists diverge significantly in their ontological and epistemological foundations.

One prominent interpretivist is the British scholar Robert W. Cox, who drew upon the critical theory tradition to develop a neo-Marxist approach for studying global power relations. Cox rejected the possibility of theory-neutral inquiry, arguing instead that theory is always created for someone and for some purpose. His approach emphasizes the intersubjective construction of knowledge and highlights how prevailing power structures limit dissent.

Similarly, the American theorist Richard K. Ashley pioneered post-structuralist analysis in IR, building on post-positivist philosophy to problematize key assumptions in mainstream IR theory. Ashley contends that the sovereign state should not be taken as the natural unit of analysis, but rather critically examined as a discursive construction. His anarchic standpoint rejects the possibility of objective, universal knowledge claims, emphasizing instead the contextual and power-laden nature of knowledge production.

Both Cox and Ashley adopt reflective approaches that seek to problematize and unpack the intersubjective construction of knowledge about international politics. Their research agendas are oriented towards critical theorization rather than empirical testing.

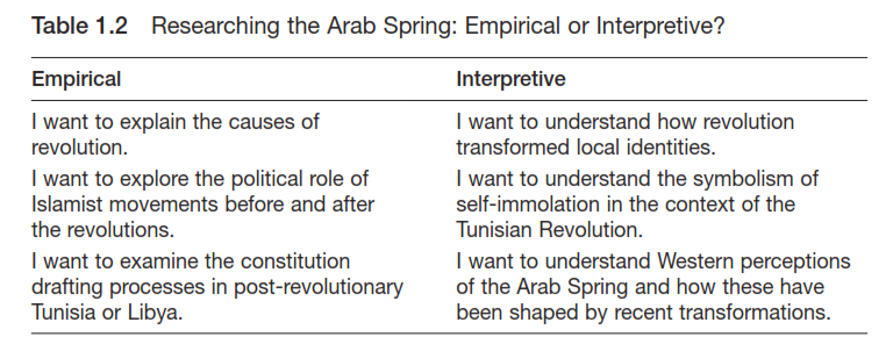

Example of Empirical and Interpretive Way of Thinking

Arab Spring

From Theory to Method: Research Choices

Research is inherently a journey of decision-making. Right from the inception of the research process, students grapple with choices that ultimately shape the nature and direction of their research essay.

When selecting a research topic, students face the critical task of transforming a broad area of interest into a precise, manageable research question. This necessitates a thorough review of existing literature, identifying gaps or uncertainties that warrant further exploration.

The decision-making process extends to the choice of research methodology and theoretical approach. Whether opting for quantitative or qualitative methods, or navigating between positivist and interpretivist epistemologies, students must carefully weigh the implications as these choices define the research design and guide data collection.

As findings emerge, students encounter additional choices in analyzing and interpreting them. These decisions involve selecting appropriate theoretical frameworks, assigning meaning to results, drawing sound conclusions, and pinpointing implications. The challenge lies in presenting the analysis logically and rigorously, aligning it seamlessly with the overarching research aims.

In essence, research is a series of decisions at every juncture. The ability to scrutinize options and articulate justifications is paramount for crafting a coherent, robust, and relevant research essay. Beginning with a well-defined and focused research question lays a sturdy foundation, empowering students to navigate the complexities of research through thoughtful and strategic decision-making.