Institution In International Security

Regional Security Structures

| Realist Definition | Alternative Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Alliance / collective defense Structures whereby regional actor seek to ally themselves with other like-minded states against a perceived common threat / enemy. Members can influence each other’s security-policy decision making process Example: NATO, US-Japan Mutual Security Treat, ANZUS |

Common security Structures whereby superpower rivals acknowledge that unilateral security is no longer possible as states are increasingly economically, culturally, politically, and military interdependent Example: Warsaw Pact, European Neutral, Japan, 3rd World Pact |

| 2. | Collective Security Structures whereby the commitment is to respond to an unknown / unspecified aggressor in support of an unknown victim Members agree to use peaceful means to settle their disputes and to act collectively to prevent / remove any threat to the peace & stability of the individual states Example: UN |

Comprehensive Security Structure whereby states expand it’s understanding of security to include non-military issues Example: Japanese security policy, ASEAN concept of national resilience |

| 3. | Concert Security Structures whereby only the great powers work together to prevent aggression Members are work together to resolves disputes / crises through informal negotiation | Example: Concert of Europe in the Post-Napoleonic Europe of the 19th century |

Cooperative Security Structures whereby states behaviors’ about security changes from one of competition with other states to cooperate with those states Example: Canada & Australia’s approach to security, workshops on managing potential conflicts in the South China Sea |

Alliances

Alliances is a formal or informal relationship of security cooperation between two or more sovereign states in form of bilateral or multilateral agreements to provide some element of security to the signatories

Example:

- NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization)

- SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Organisation)

- CSTO (Collective Security Treaty Organization)

- FPDA (Five Power Defence Arrangements)

- ANZUS (Australia, New Zealand, and United States Security Treaty)

- U.S. Bilateral Alliance (Israel, Japan, Philippines, South Korea)

Regional Institution

The end of the Cold War brought a seismic shift in the global order, with regional alliances and institutions adapting to the disappearance of the Cold War bipolar world. With the Soviet Union’s collapse, regional security dynamics underwent transformation. From the 1990s onwards, while some institutions dissolved or reinvented their purpose, like the Warsaw Pact, others expanded their membership and scope, as in the case of NATO and the EU. The post-Cold War period has witnessed the ascendance of regional security frameworks centered around shared identities, interests, and perceived threats.

States engage in regional security institutions as responses to power shifts in the international system and see them as tools for confidence-building, conflict prevention, and upholding sovereignty. These institutions encompass formal alliances like ANZUS and informal groupings like ASEAN, aiming to tackle both traditional and non-traditional security threats. Their effectiveness varies based on commitment to cooperation, resources, mandate, and cohesion. Regional institutions complement the UN’s global approach to peace and security, helping to manage conflicts and build trust locally. However, they face limitations when member states’ interests diverge or when crises spill beyond regional boundaries.

Security activities of regional institutions

- Confidence-building measures

- Defense of sovereignty & territorial integrity

- Peacekeeping

- Security & economic development

- Peaceful settlement of disputes

- Foreign policy coordination

- Security cooperation

- Resolution of border disputes

- Disarmament & arms control

- Preventive diplomacy

- Freedom, security, & justice

- Safeguarding of national rights

- Combating terrorism, drugs, & weapons trafficking

- Peace enforcement

- Election monitoring

- Institution building

- Non-proliferation

Example:

- Africa

- OAU/AU, IGADD/IGAD, ECOWAS, SADCC/SADC, CEMAC

- Europe

- EC/EU, WEU, NATO, (Warsaw Pact) OSCE, CIS, CSTO

- Asia

- (SEATO), ASEAN, SAARC, ARF, SCO, CACO, ICO

- Middle East

- LAS, (CENTO), GCC, AMU, (ACC), ECO, ICO

- Americas

- OAS, CARICOM, OECS, MERCOSUR

- Australasia

- ANZUS, SPF/PIF

United Nations Security Role

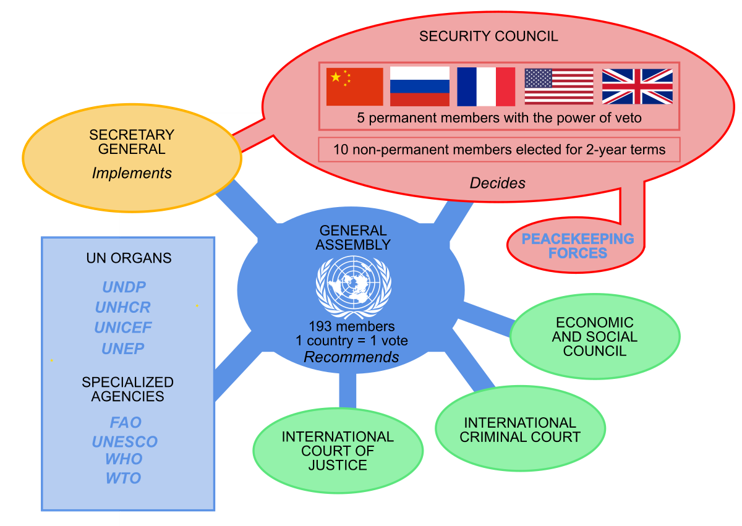

The United Nations was founded in 1945 with the aim of maintaining international peace and security. Its founding charter outlines principles such as resolving disputes peacefully, refraining from the use of force in international relations, and promoting human rights and social progress.

The UN’s main security roles are carried out by the Security Council, which is charged with maintaining peace, authorizing military action, enacting economic sanctions, and admitting new members. The Security Council has faced challenges in recent decades as the nature of conflicts has changed. During the Cold War, it was often paralyzed by vetoes from the US and USSR. In the post-Cold War era, most conflicts have been intrastate rather than between countries. This poses difficulties for traditional UN peacekeeping operations, which rely on host state consent.

Nuclear Institutions

The global nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime faced significant challenges during the Cold War era and continues to grapple with complex issues today.

The centerpiece of this regime is the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Opened for signature in 1968, it aims to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons technology while enabling the peaceful use of nuclear energy. Key tenets include non-proliferation obligations, disarmament commitments for nuclear weapon states, and rights to peacefully use nuclear technology.

During the Cold War, the NPT succeeded in limiting proliferation to a few states beyond the initial nuclear powers. However, India, Pakistan, Israel, and South Africa developed nuclear weapons while remaining outside the NPT. The end of the Cold War brought deeper cuts to U.S. and Russian arsenals, but global nuclear stockpiles remain substantial.

In recent decades, complex challenges have emerged. North Korea withdrew from the NPT in 2003 and tested nuclear devices. Iran engaged in nuclear activities outside of IAEA safeguards, leading to international sanctions until the 2015 nuclear deal. Tensions persist around existing arsenals and proliferation risks.

Nuclear security also faces threats from non-state actors seeking nuclear materials along with cyberattacks on nuclear infrastructure. Multilateral cooperation through institutions like the NPT is vital but faces pressure from lack of trust and withdrawals. Creative supplementary approaches like the Iran deal reveal the need for flexibility alongside institutional frameworks to address 21st century nuclear challenges.

Private Security Industry

The private security industry has grown substantially since its emergence in the 1960s, with companies like Blackwater gaining notoriety for controversial incidents in Iraq and elsewhere. This proliferation of private companies providing security services internationally has raised important questions about the state’s traditional monopoly over violence and the implications of outsourcing security functions to private actors.

The rise of private military and security companies (PMSCs) like Blackwater stems from states seeking to fill gaps in capacity during foreign interventions. By hiring private contractors for security, states can avoid potential domestic political blowback from military casualties. However, this reliance on PMSCs has drawn criticism when contractors have engaged in human rights abuses or escalated conflicts while evading accountability. The lack of transparency and oversight associated with private security exports poses risks of undermining foreign policy and empowering non-state groups.

The global private security industry exhibits the characteristics of a transnational market, with services flowing across borders in response to demand. States have struggled to extend regulatory control over PMSCs operating abroad. The implications of private security’s growth include shifting power dynamics in the realm of violence, reduced state accountability and legitimacy, and new relationships between commercial actors and the foreign policy establishment.

As private security continues to expand into spheres traditionally dominated by states, important normative and practical questions persist around regulating its export, prosecuting contractor crimes, and balancing public and private interests. The proliferation of PMSCs represent a shift in how violence and security are provided globally, with complex repercussions for international relations and governance.