Globalization And Global Politics

Summary Video

Material’s recommendation before reading the study guide

Introduction

Globalization is fundamentally defined by increased worldwide interconnectedness and interdependence. This is evident in the operations of more than 45,000 international NGOs, the ability to connect like-minded individuals across the planet, and a growing recognition of global problems demanding global solutions.

Trade emerges as a major driver of globalization, with over $4 trillion flowing daily through foreign exchange markets. Transnational corporations contribute to over a quarter of world output and two-thirds of world trade, highlighting their role in weaving an intricate web of global business. Under conditions of political globalization, nation-states find themselves increasingly embedded within a thickening web of international relationships and decision-making.

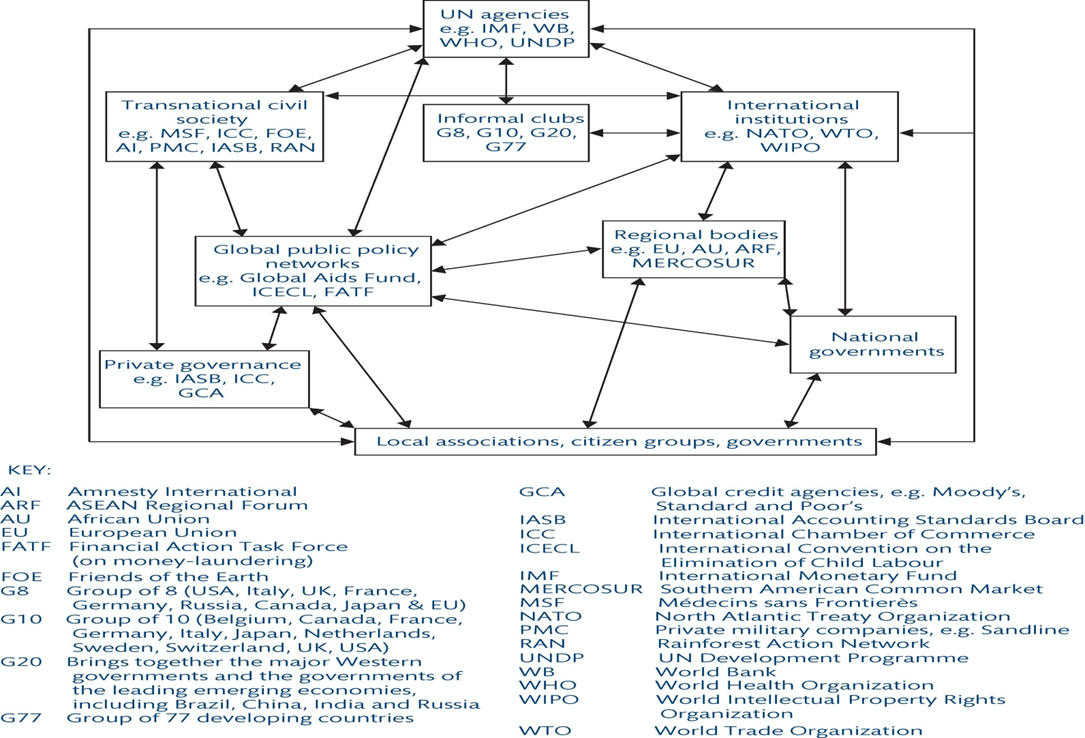

Under conditions of political globalization, states are increasingly embedded in thickening and overlapping worldwide web

Worldwide Web

Globalization in Practice

Trade emerges as a major driver of globalization, with over $4 trillion flowing daily through foreign exchange markets and transnational corporations contributing to over a quarter of world output and two-thirds of world trade.

Examining a case study, the production of the iPhone exemplifies globalization through its intricate supply chain and manufacturing process spanning multiple countries. Apple’s products and components are sourced from over 200 suppliers across North America, Europe, and Asia.

Final assembly takes place in Shenzhen, China at Foxconn’s Longhua plant, which employs hundreds of thousands of workers and produces half of the world’s iPhones. Apple has additionally outsourced manufacturing to suppliers in Brazil, India, Malaysia, South Korea, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Apple’s strategic decision to manufacture in various global locations underscores the global nature of its operations, benefiting from cost efficiencies, skilled labor, advanced manufacturing capabilities, and diverse regulatory environments across different countries. Globalized production allows Apple to leverage the comparative advantages of different locations while maintaining control over quality, intellectual property, and branding.

Theoretical Views

Globalization can be conceptualized as a shift from discrete national states to a shared social space, where central aspects of human affairs are organized on a transnational or global scale. This process is characterized by “time-space compression” and “deterritorialization” according to some theorists.

Time-space compression refers to how advancements in technology, transportation, and communication have effectively shrunk distances and accelerated the pace of interaction between places and events across the globe. Developments like the Internet and air travel have enabled rapid flows of information, people, goods, and services in ways that collapse geographical limitations.

Deterritorialization involves the weakening of ties between culture, identity, and place. Globalization detaches social and economic activities from specific locations, so they are organized transnationally rather than confined within state borders and territories. Deterritorialization erodes traditionally fixed national affiliations and activities.

These interrelated concepts underscore how globalization reshapes traditional conceptions of time, space, borders, distance, and geography. Theorists emphasize a fundamental shift in worldwide social organization, transcending discrete nation-states toward integrated transnational processes and interactions. Globalization compresses our sense of space and time while deterritorializing previously geographically-rooted phenomena.

Criticisms

The process of globalization has faced critiques from various perspectives. Some argue that globalization is too often synonymous with “OECD-ization”, meaning it is predominantly linked to Western capitalism and US economic and political hegemony. In this view, globalization serves the interests and ideological foundations of Western developed economies, expanding markets for their goods and services.

Linked to this is the notion that globalization rides on the coattails of Americanization, the spread of American economic power, culture, and values on a global scale. US multinational corporations are major drivers of market expansion and consumer culture around the world. Critics contend globalization risks being conflated with, or subsumed under, US interests.

In addition, some skeptics point out that globalization relies on a stable economic environment and could potentially be derailed by major economic shocks or crises. The global financial crisis of 2008 revealed the fragility of global economic integration, as credit dried up and international trade declined sharply. Sudden economic contractions could lead nations to turn inward, undermining the globalization project.

This perspective also argues that globalization is an uneven process that has produced winners and losers. While supporters highlight absolute increases in global living standards, critics maintain that relative gaps between rich and poor countries have persisted or worsened in many cases. They argue that globalization’s rewards are spread unevenly, and concentrated among wealthy nations and individuals.

Inequalities

The globalization process is inherently asymmetrical and uneven, fostering inequalities across various fields of human activity. It is institutionalized through new infrastructures of control and communication, exemplified by organizations like the WTO and transnational corporations.

Specifically, globalization has created winners and losers. While some groups, countries, and individuals have greatly benefited from increased global interconnectedness, others have been left behind or disadvantaged.

Economically, globalization has enabled companies to access wider markets and consumers. But the gains have not been evenly distributed, with advanced economies often reaping greater rewards. Developing countries seeking foreign investment and exports can be vulnerable to global economic shocks and terms of trade that favor the West.

Furthermore, economic integration has often favored the mobility of capital over labor. Corporations can move factories and jobs overseas to access cheaper labor markets, leaving displaced and marginalized workers in their home countries.

The new infrastructure of economic globalization - free trade rules, intellectual property rights, and transnational corporations - reflects power structures that favor dominant states and commercial interests. Institutions like the World Trade Organization promote a neoliberal economic model that developing countries struggle to adjust to.

Culturally, globalization enables worldwide exposure and exchange of ideas, art, and media. However critics argue it can lead to cultural imperialism, homogenization, and loss of local identity. Powerful Western cultural industries and brands can overwhelm indigenous culture. English has become the global lingua franca online, marginalizing other languages.

While globalization connects the world, the benefits have accrued asymmetrically. Addressing inequalities remains an ongoing challenge. More equitable global integration requires inclusive policies and new forms of global cooperation and governance.

Global Politics

The long-established Westphalian principles of sovereignty, autonomy, and territoriality that have traditionally governed the realm of global politics are fundamentally challenged under conditions of contemporary globalization.

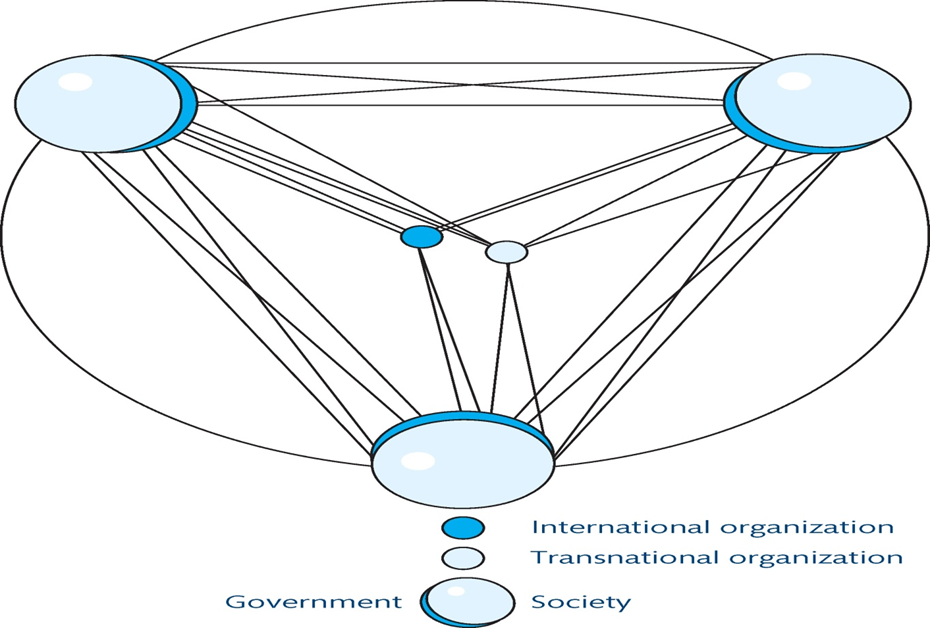

Nation states today find themselves increasingly embedded within complex webs of multilateral and transnational decision-making processes and institutions that diffuse sovereignty and autonomy. This contributes to the steady emergence of an evolving global governance complex.

Where previously states interacted mainly bilaterally within an anarchic international system, they now negotiate and cooperate within diverse multilateral forums and regimes that transcend territorial boundaries. States thereby sacrifice portions of sovereignty and autonomy to partake in joint decision-making.

Notable examples include the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the International Criminal Court, and the European Union. While such organizations aim to foster global cooperation, the lack of formal accountability mechanisms and resource inequalities between member states pose risks.

The diversity of voices in global governance creates opportunities for an emerging transnational civil society. However, the absence of electoral accountability requires caution to ensure all affected voices are equitably represented.

Overall, globalization compels states to become more embedded participants in a dense, overlapping, and multidimensional system of global governance. This steady shift challenges conventional notions of sovereignty, autonomy and territoriality.

Global Governance

The emergence of globalization has led to the rise of a global governance complex involving various multilateral institutions and organizations that work to address issues on a worldwide scale. Key examples include the United Nations, World Trade Organization, World Health Organization, and World Bank. While nation-states still retain sovereignty, they find themselves increasingly embedded within international and transnational networks.

This system aims to foster cooperation between countries to tackle global challenges like climate change, pandemics, financial crises, terrorism, and more. It brings together not just states but also non-state actors like NGOs, companies, and civil society groups, contributing to a diverse transnational civil society. Advocates argue that global issues require global solutions and coordination.

However, Critics contend that global governance lacks formal accountability and transparency. There are vast inequalities between participants in terms of resources and influence. Powerful countries and corporations hold greater sway in shaping rules and norms. Poorer nations have limited ability to advocate their interests. With no world government, the enforcement of agreements depends on the voluntary compliance of sovereign states.

Overall, while global governance holds promise in coordinating collective action, its decentralized and voluntary nature poses challenges. Striking an equitable balance of interests and ensuring all stakeholders have a voice remains an ongoing task. Democratizing global governance to make it more inclusive and accountable remains vital.

The Global Governance Complex