Domestic Politics: Two Level Games

What is two-level game?

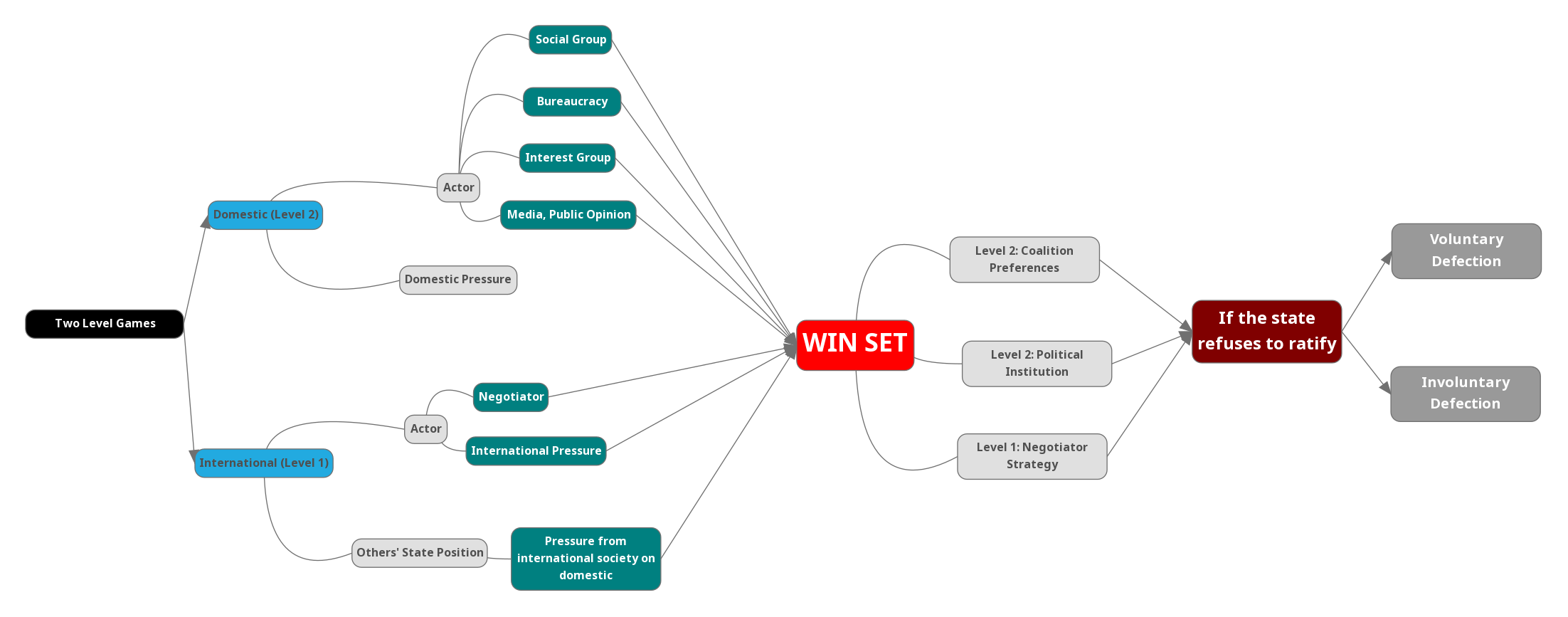

The “two-level game” is a theoretical approach about how state’s representative in negotiations between states shape their state’s foreign policy by two stages, that is:

1) bargaining between international negotiators , leading to a tentative agreement (Level I) 2) separate discussions within each domestic or national group of constituents about whether to ratify the agreement (Level II).

The win-set refers to the set of all possible Level I agreements that would gain the necessary majority among the constituents when simply voted up or down. It is important for understanding the likelihood of reaching an agreement and the distribution of joint gains from the international bargain.

The size of the “win-set” of feasible agreements depends on the distribution of power, preferences, and possible coalitions among Level II constituents. The two-level game is a complex process in which moves that are rational for a player at one level may be impolitic for that same player at the other level. The requirement that any Level I agreement must be ratified at Level II imposes a crucial theoretical link between the two levels.

Process of Two-Level Game

The two-level game process, as proposed by Robert D. Putnam, involves two stages: Level I and Level II.

-

Level I: This stage entails bargaining between negotiators from different states, leading to a tentative mutual agreement. The actors’ in this level is: parties leader, ministry, etc.

-

Level II: In this stage, separate discussions occur within each group of constituents about whether to ratify the agreement reached at Level I. The actors’ in this level is between negotiator and domestic actors (legislative members’, interest group, etc)

The process is sequential, with the requirement that any Level I agreement must be ratified at Level II, thereby creating a crucial theoretical link between the two levels. The size of the “win-set,” which refers to the set of all possible Level I agreements that would gain the necessary majority among the constituents when simply voted up or down, is a key determinant of the possibility of reaching an agreement. The win-set depends on the distribution of power, preferences, and possible coalitions among Level II constituents, and it affects the likelihood of reaching an agreement and the distribution of joint gains from the international bargain.

Win-Sets Determinant

The concept of “win-set” in the two-level games theory is a crucial determinant of the possibility of reaching an agreement in international negotiations. The win-set refers to the set of all possible Level I agreements that would gain the necessary majority among the constituents when simply voted up or down. It is influenced by several factors, including:

- Distribution of power and preferences: The size of the win-set depends on the distribution of power, preferences, and possible coalitions among Level 1 constituents.

- Domestic political constraints: The preferences and power of domestic actors, such as interest groups, political parties, bureaucrats, and the general public, can affect the size of the win-set.

- Overlap of win-sets: The likelihood of reaching an agreement is increased if the win-sets of the negotiating parties overlap, meaning that there is some common ground on which they can agree. Conversely, if the win-sets do not overlap, the negotiations are more likely to break down.

What if state’s failed to ratify the agreement?

The ratification process does not guarantee the implementation of state agreements. The state has full authority to comply or disobey the agreement. There are 2 types of rejection:

- Voluntary Defection (based on state egoism)

Voluntary defection in game theory refers to reneging by a rational egoist in the absence of enforceable contracts, as seen in the prisoner’s dilemma and other dilemmas of collective action.

The reason for this rejection makes the situation “the absence of hierarchy” a justification for all egoist state actions. For example: the US decision not to ratify the Kyoto Protocol seems legitimate even though environmental damage is getting worse due to industrialization.

- Involuntary Defection (the state’s inability to fulfill the agreement)

Involuntary defection refers to the behavior of an agent (states) who is unable to deliver on a promise because of failed ratification.